Gower Bell

Frederic Allan Gower was an American entrepreneur

who, for a while, operated a Bell franchise in the U.S state of New England. He

toured and lectured with Bell and Watson before heading off to England in the

early 1880s. Here he completed the design that became the British Post Office

standard for many years.

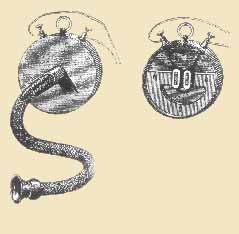

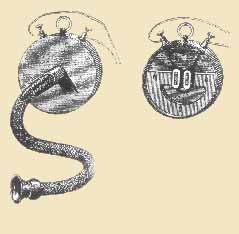

The unusual style of his phone was due to the technology of the times. Bell’s

patents made it necessary to develop alternative designs of transmitters and

receivers. For a receiver, Gower produced a version of the Watchcase Receiver.

It used a fairly powerful semicircular magnet with a bobbin wound around the

end of each pole. This design was not particularly efficient compared with

the Bell receiver, but Gower made it much bigger than usual and used a very

large tinned iron diaphragm. This gave quite adequate reception but its size

(more than four inches across) meant that the receiver had to be mounted inside

the case of the phone. Sound was fed from here to the ears by long rubber

tubes. He patented this part of the design in December 1880 before he left

the United States. This caused some ill feeling with Bell and Watson, and

may have helped to encourage his move to Europe. Watson was quoted as saying

“...he made some small modifications to Bell’s telephone, called

it the “Gower-Bell” telephone and made a fortune out of this hyphenated

atrocity”.

For a transmitter, Gower originally used a Bell-type magnetic instrument. In

Britain he quickly saw the potential of the carbon pencil microphone described

but not patented by Professor

Hughes some years earlier. This conveniently worked around the Bell

patents. After trying a number of variations, Gower settled on an eight-pencil

model. The pencils, about one and three quarters of an inch long, were held

in a star pattern by copper blocks. The multiple pencils stopped the dropout

problem experienced when a single pencil vibrated off its copper contacts. The

unit proved stable and reliable. The assembly was mounted on the back of a flat

teak sounding board roughly nine inches by five inches. This became the transmitter’s

diaphragm.

Because the diaphragm was quite thin, it was sometimes protected by another

sheet of timber mounted above it, with decorative cutouts to let the sound

in the style of Crossley phones. The cutout was quickly abandoned, and sound

pressure reached the diaphragm through a porcelain mouthpiece horn. Condensation

in the relatively cold horn caused moisture to drip onto the diaphragm, which

caused faults and gave off a bad smell. Other mouthpieces were tried in ebonite

and turned wood, but finally in the late 1890s the mouthpiece was abandoned.

The diaphragm was generally left exposed, and sometimes decorated with a painted

design.

A single trembler bell was provided to signal incoming calls, with the mechanism

concealed inside the box on early models. Only the bell and clapper protruded

from the bottom. On later models the bell was provided separately. Signalling

out was provided by a pushbutton mounted at the top of the backboard. This gave

a rather limited signalling range of a mile or so. A simple switchhook at each

side to hold the speaking tubes and a coil inside the box were all that was

needed to complete the phone. This basic design stayed unchanged through the

life of the phone, during which some thousands were produced for the British

Post Office.

Initially the phones were manufactured for the Gower Bell Telephone Company

by Charles Moseley and Sons in Manchester. In April 1881 Gower Bell amalgamated

with the United Telephone Company ( a union of the London Edison and Bell

companies) and set up a new company, the Consolidated Telephone Construction

and Maintenance Co. Ltd, to produce telephones. It not only manufactured Bell

telephones and equipment for the United Telephone Company, but made Gower

phones for the British Post Office, who in 1882 pronounced the Gower Bell

as "the best and most reliable telephone in service". The BPO was

in the unfortunate position of not being able to use Bell phones as they were

still under patent, and the BPO was becoming increasingly hostile to the Bell

companies, fearing a loss of revenue from the telegraph system.

Consolidated also made phones for a new European company, the Edison Gower-Bell

Telephone Company of Europe, Ltd. This new company held Edison’s and Gower’s

telephone patents for Europe, and was responsible for sales to all European

countries outside Britain, France, Turkey and Greece. Edison’s motivation

in this was the same as Bell’s - to expand his company’s influence

to as many countries as possible. Until the Bell patents expired, Edison needed

a phone to sell.

A magneto model is known from 1882 with a tall backboard to accommodate the

magneto generator/bellbox and battery box. This model was sold overseas for

a long time, particularly to Portugal, by the new company. Sales of Gower phones

have been noted to Spain, Portugal, Australia and Japan. In Tasmania Gower-Bells

were used on some of the first private telephone lines in the colony. Japan’s

first telephone services were provided in 1893 with 244 locally-made improved

Gower-Bells. These were converted to use Ader-type receivers instead of tubes.

In France, the Societe Generale des Telephones was formed from Societe du Telephone

Edison, the Societe du Telephone Gower, and the Soulerin Company. In Argentina,

Compañía de Teléfonos Gower-Bell began operations. Some

of these foreign companies used Ader or Pony Crown receivers where the Bell

patents were not a problem.

The British Post Office refitted

their Gowers with simpler double-pole Bell receivers instead of the Gower tubes

as soon as the Bell patents expired. The tubes needed a high level of maintenance,

and the Bell receivers had better public acceptance. The name “Gower Bell”

appears to have been only a marketing move by Gower, as this later BPO conversion

was the first time the phone had anything to do with Bell.

By the turn

of the century the Gower Bell had dropped into disuse, replaced by the more modern

and efficient phones using standard Bell and Edison technology. The handset had

been introduced by Ericsson and widely copied by others, and the Gower had become

a rather clumsy relic of the past.

Gower was successful enough in the

short life of his business that he was comfortably off and was able to indulge

his hobbies. He lost his life in an attempt to fly a hot air balloon across the

English Channel.

Bibliography:

Original article for

the ATCS Newsletter, January 1992, Havyatt R.

Further information from

Christiansen R. Internet site, (no longer available)

Allsop F. C. “Telephones - Their Construction and Fitting:”

- London 1894

Poole J “The Practical Telephone Handbook” -

New York 1912

Moyall A. “Clear Across Australia” - Melbourne

1984

Herbert T. E. & Proctor W. S. “Telephony Vol 1” -

London 1932

http://park.org/Japan/NTT/MUSEUM/html_ht/HT890020_e.html

http://edison.rutgers.edu/ecopart2.htm

http://bocc.ubi.pt/pag/sousa-helena-chap-5-evolution.html

http://www.sonria.com/bim/modules.php?op=modload&name=News&file=article&sid=4761&mode=thread&order

=0&thold=0

Gower Bell Phones Gower Bell Phones  If you have reached this page through a Search Engine, this will take you to the front page of the website If you have reached this page through a Search Engine, this will take you to the front page of the website

|