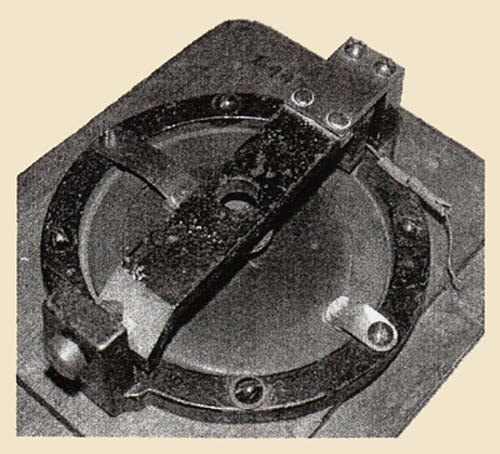

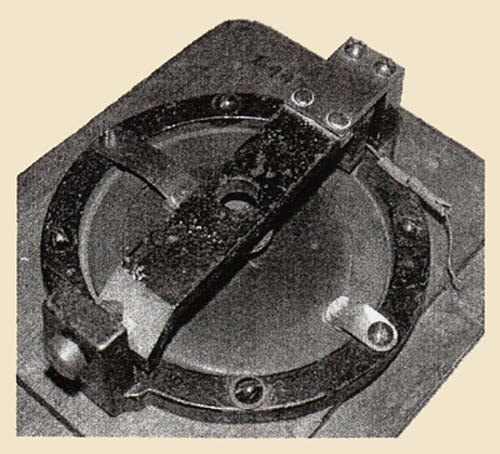

So What was different about the Blake?  Not much, according to Allsop (1891, 1892), Thompson (1883) and Aitken (1939) - all non-Bell people. When the patent claims are all pulled apart, Blake had a single-contact, variable resistance, carbon microphone. Why it worked better than some over short lines (no single contact could carry much current before pitting or fusing) was due to the (arguably unique) arrangement of the contact points on springs that "floated". The platinum side was always against the Diaphragm - but not attached to it, (as with Edison and others) being on a separate leaf spring, attached to the (moving) cast arm, or bar, as part of an insulated spring pile. The carbon side bore against it, on its own flat spring. The pressure put on the contact itself to keep the points together was supplied by the heavy, short, flat spring joining the cast metal upper arm or bar to the frame. An adjusting screw with a tapered point bearing on the angle of that bar meant the pressure on the contact-pair, pressing against the diaphragm, could be fine tuned infinitely. Not much, according to Allsop (1891, 1892), Thompson (1883) and Aitken (1939) - all non-Bell people. When the patent claims are all pulled apart, Blake had a single-contact, variable resistance, carbon microphone. Why it worked better than some over short lines (no single contact could carry much current before pitting or fusing) was due to the (arguably unique) arrangement of the contact points on springs that "floated". The platinum side was always against the Diaphragm - but not attached to it, (as with Edison and others) being on a separate leaf spring, attached to the (moving) cast arm, or bar, as part of an insulated spring pile. The carbon side bore against it, on its own flat spring. The pressure put on the contact itself to keep the points together was supplied by the heavy, short, flat spring joining the cast metal upper arm or bar to the frame. An adjusting screw with a tapered point bearing on the angle of that bar meant the pressure on the contact-pair, pressing against the diaphragm, could be fine tuned infinitely.

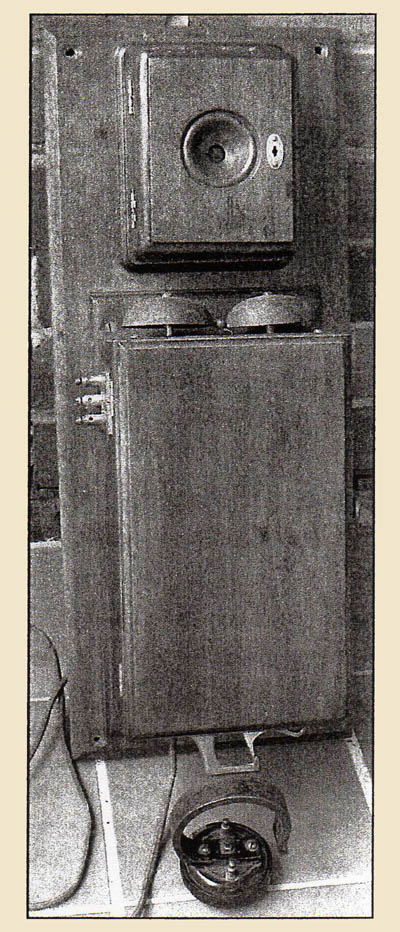

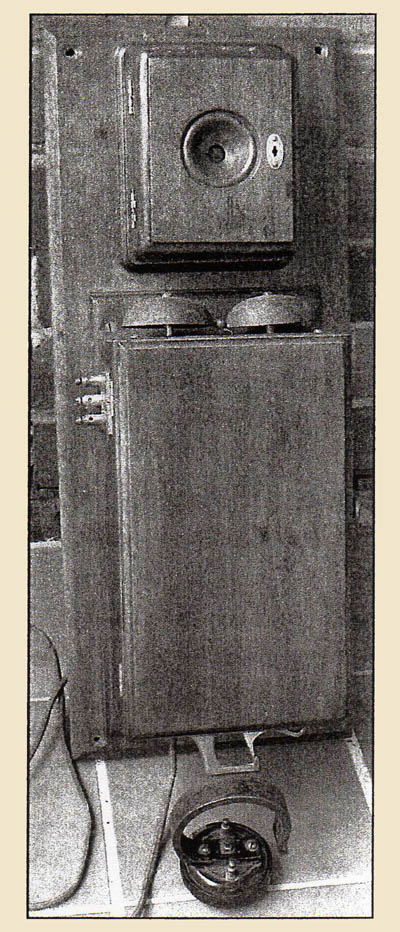

This was seen as new and novel by Allsop (1891) because if properly adjusted the system would eliminate the "crashing" of contact-breaking, which spoiled other designs, including carbon pencil types. Lockwood (1882) sums it up: The Blake was a "legitimate offspring of the (Hughes) microphone… the same idea seems to have occurred about the same time to many other minds …but Blake assisted by several other experts of the Bell Tel. Co. … was the one to make it work". Blakes in Australia  Manufacturing rights outside USA usually went to the Bell affiliate in that country - and so in Europe the Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company of Antwerp made Blakes. Most of those now found in Australia and New Zealand come from there, although examples by Consolidated Telephone Construction and Maintenance Co (UK, manufacturing under license from National) and from Western Electric (USA) , as well as other odd ones also turn up. The first telephones used on Melbourne exchanges included a two-box Blake by Western Electric with a "Watson" pattern generator on the lines of early medical shocking machines (coils spun in the field of a huge horseshoe magnet, curved handle on the front). Later models used the Siemens pattern armature in the usual generator configuration. The US (Bell) Blake transmitter had a cast iron frame painted black. The European Bell Antwerp models had a lighter, cast brass frame, though other parts are virtually identical. Early models had a circular stamp in the wood, on the right side of the box, reading "Bell Telephone Manufacturing Co." with or without the word Antwerp and/or some stars. Some just had "BTMC" alone. Others were plain. Consolidated (UK) Blakes had the cast iron frames with either wood-stamping or transfer badges on the front door. Antwerp Blake box edge-mouldings are standard American furniture pattern, but the early American WE models had various edge profiles - some beveled only on the base. Manufacturing rights outside USA usually went to the Bell affiliate in that country - and so in Europe the Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company of Antwerp made Blakes. Most of those now found in Australia and New Zealand come from there, although examples by Consolidated Telephone Construction and Maintenance Co (UK, manufacturing under license from National) and from Western Electric (USA) , as well as other odd ones also turn up. The first telephones used on Melbourne exchanges included a two-box Blake by Western Electric with a "Watson" pattern generator on the lines of early medical shocking machines (coils spun in the field of a huge horseshoe magnet, curved handle on the front). Later models used the Siemens pattern armature in the usual generator configuration. The US (Bell) Blake transmitter had a cast iron frame painted black. The European Bell Antwerp models had a lighter, cast brass frame, though other parts are virtually identical. Early models had a circular stamp in the wood, on the right side of the box, reading "Bell Telephone Manufacturing Co." with or without the word Antwerp and/or some stars. Some just had "BTMC" alone. Others were plain. Consolidated (UK) Blakes had the cast iron frames with either wood-stamping or transfer badges on the front door. Antwerp Blake box edge-mouldings are standard American furniture pattern, but the early American WE models had various edge profiles - some beveled only on the base.

Locks also varied - a few had actual mortice locks (as in the Melbourne Museum example) , other had a more familiar rotating catch with keyhole escutcheon on the front - similar to twin boxes. Wood was mainly black walnut, but a few US models came out in cherry wood or other timbers. Mouthpieces were usually a semi-circular scallop in the wood - though some had a straight conical scallop. There are many other minor variations , depending on the country / company of manufacture. Blakes were also fastened inside the door of complete one-box phones - more compact. Other were cased in neat metal cans (see Fig. 9) to hang in front of switchboard operators - obscuring less of the board than a box. There was even an experimental "double contact" version, with two adjusting screws and contact sets. This rarity is held in the Scienceworks collection of the Melbourne Museum. So, Why the Blake again?  Blakes dominated telephony from 1878 to about 1890, though many were in use long after. Few genuine original mechanisms are found today (beware the expert copies) \, because when superior , granular carbon "Hunnings" pattern transmitters became available many Blakes were converted. Sometimes a big hole was bored through the mouthpiece scallop and the internal "step" was planed off to accommodate the shaft of an external, nickeled Hunnings type. Otherwise the door was (luckily) left intact and a field conversion was done by changing the Blake mechanism for a replacement, internal, Hunnings with appropriate hardware. Thus the boxes turn up more often than the transmitter mechanism. Blakes dominated telephony from 1878 to about 1890, though many were in use long after. Few genuine original mechanisms are found today (beware the expert copies) \, because when superior , granular carbon "Hunnings" pattern transmitters became available many Blakes were converted. Sometimes a big hole was bored through the mouthpiece scallop and the internal "step" was planed off to accommodate the shaft of an external, nickeled Hunnings type. Otherwise the door was (luckily) left intact and a field conversion was done by changing the Blake mechanism for a replacement, internal, Hunnings with appropriate hardware. Thus the boxes turn up more often than the transmitter mechanism.

Blake's transmitter was an improvement, not an innovation. There was in reality nothing actually new - except the very efficient arrangement whereby the heavy top bar, on a leaf spring, could be screw-adjusted to accurately tension the two contact springs against the diaphragm, and so minimize contact-breaking. Allsop (1891, 1892) examines the patent and finds little difference in principle with other microphones - and, as we saw, it could be just an improved Reis model, by some analyses. Both Blake and Berliner continued inventing, but the significance of their joint contribution to commercialising Blake's transmitter cannot be underestimated. Money, power, and a burning need by what became the most powerful of the telephone interests put the Blake into history - but the Blake also "made" the Bell company, for Western Union had very nearly destroyed Bell when it arrived on the scene. As Hall (2003) wrote: "Bell Telephone needed Blake's transmitter , and Blake knew just how much".

Left: Early Ericsson transmitter was mounted onto the Blake box as an upgrade.

Page 5 Page 5

Page 3 Page 3

|

Not much, according to Allsop (1891, 1892), Thompson (1883) and Aitken (1939) - all non-Bell people. When the patent claims are all pulled apart, Blake had a single-contact, variable resistance, carbon microphone. Why it worked better than some over short lines (no single contact could carry much current before pitting or fusing) was due to the (arguably unique) arrangement of the contact points on springs that "floated". The platinum side was always against the Diaphragm - but not attached to it, (as with Edison and others) being on a separate leaf spring, attached to the (moving) cast arm, or bar, as part of an insulated spring pile. The carbon side bore against it, on its own flat spring. The pressure put on the contact itself to keep the points together was supplied by the heavy, short, flat spring joining the cast metal upper arm or bar to the frame. An adjusting screw with a tapered point bearing on the angle of that bar meant the pressure on the contact-pair, pressing against the diaphragm, could be fine tuned infinitely.

Not much, according to Allsop (1891, 1892), Thompson (1883) and Aitken (1939) - all non-Bell people. When the patent claims are all pulled apart, Blake had a single-contact, variable resistance, carbon microphone. Why it worked better than some over short lines (no single contact could carry much current before pitting or fusing) was due to the (arguably unique) arrangement of the contact points on springs that "floated". The platinum side was always against the Diaphragm - but not attached to it, (as with Edison and others) being on a separate leaf spring, attached to the (moving) cast arm, or bar, as part of an insulated spring pile. The carbon side bore against it, on its own flat spring. The pressure put on the contact itself to keep the points together was supplied by the heavy, short, flat spring joining the cast metal upper arm or bar to the frame. An adjusting screw with a tapered point bearing on the angle of that bar meant the pressure on the contact-pair, pressing against the diaphragm, could be fine tuned infinitely. Manufacturing rights outside USA usually went to the Bell affiliate in that country - and so in Europe the Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company of Antwerp made Blakes. Most of those now found in Australia and New Zealand come from there, although examples by Consolidated Telephone Construction and Maintenance Co (UK, manufacturing under license from National) and from Western Electric (USA) , as well as other odd ones also turn up. The first telephones used on Melbourne exchanges included a two-box Blake by Western Electric with a "Watson" pattern generator on the lines of early medical shocking machines (coils spun in the field of a huge horseshoe magnet, curved handle on the front). Later models used the Siemens pattern armature in the usual generator configuration. The US (Bell) Blake transmitter had a cast iron frame painted black. The European Bell Antwerp models had a lighter, cast brass frame, though other parts are virtually identical. Early models had a circular stamp in the wood, on the right side of the box, reading "Bell Telephone Manufacturing Co." with or without the word Antwerp and/or some stars. Some just had "BTMC" alone. Others were plain. Consolidated (UK) Blakes had the cast iron frames with either wood-stamping or transfer badges on the front door. Antwerp Blake box edge-mouldings are standard American furniture pattern, but the early American WE models had various edge profiles - some beveled only on the base.

Manufacturing rights outside USA usually went to the Bell affiliate in that country - and so in Europe the Bell Telephone Manufacturing Company of Antwerp made Blakes. Most of those now found in Australia and New Zealand come from there, although examples by Consolidated Telephone Construction and Maintenance Co (UK, manufacturing under license from National) and from Western Electric (USA) , as well as other odd ones also turn up. The first telephones used on Melbourne exchanges included a two-box Blake by Western Electric with a "Watson" pattern generator on the lines of early medical shocking machines (coils spun in the field of a huge horseshoe magnet, curved handle on the front). Later models used the Siemens pattern armature in the usual generator configuration. The US (Bell) Blake transmitter had a cast iron frame painted black. The European Bell Antwerp models had a lighter, cast brass frame, though other parts are virtually identical. Early models had a circular stamp in the wood, on the right side of the box, reading "Bell Telephone Manufacturing Co." with or without the word Antwerp and/or some stars. Some just had "BTMC" alone. Others were plain. Consolidated (UK) Blakes had the cast iron frames with either wood-stamping or transfer badges on the front door. Antwerp Blake box edge-mouldings are standard American furniture pattern, but the early American WE models had various edge profiles - some beveled only on the base. Blakes dominated telephony from 1878 to about 1890, though many were in use long after. Few genuine original mechanisms are found today (beware the expert copies) \, because when superior , granular carbon "Hunnings" pattern transmitters became available many Blakes were converted. Sometimes a big hole was bored through the mouthpiece scallop and the internal "step" was planed off to accommodate the shaft of an external, nickeled Hunnings type. Otherwise the door was (luckily) left intact and a field conversion was done by changing the Blake mechanism for a replacement, internal, Hunnings with appropriate hardware. Thus the boxes turn up more often than the transmitter mechanism.

Blakes dominated telephony from 1878 to about 1890, though many were in use long after. Few genuine original mechanisms are found today (beware the expert copies) \, because when superior , granular carbon "Hunnings" pattern transmitters became available many Blakes were converted. Sometimes a big hole was bored through the mouthpiece scallop and the internal "step" was planed off to accommodate the shaft of an external, nickeled Hunnings type. Otherwise the door was (luckily) left intact and a field conversion was done by changing the Blake mechanism for a replacement, internal, Hunnings with appropriate hardware. Thus the boxes turn up more often than the transmitter mechanism.